Valentine Obienyem

In Christian theology, the Trinity operates in harmonious distinction: the Father as Creator, the Son as Redeemer, and the Holy Spirit as Sanctifier. Though worlds apart in essence and gravity, public life sometimes offers its own triadic echoes – not of sanctity, but of human roles in the unfolding moral drama of a nation. In Nigeria today, we witness a secular parallel: inspiration, decline, and distraction. This is not, heaven forbid, a comparison between the divine and the fallible, but a structural illustration – a metaphorical lens through which we might understand the state of our public conscience. Each role, however imperfectly, finds its embodiment in a figure whose voice now shapes, distorts, or burdens the national conversation.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie inspires. With the grace of thought and the courage of conviction, she offers clarity in an age of confusion. Wole Soyinka, once the thunderous conscience of a nation, now sadly stands as a figure of fallen grandeur – still towering, but often greeted with a sigh rather than reverence. And Reno Omokri? He is the noisy one, the perpetual distraction, like a jester mistaking folly for wisdom.

However I choose to compare, and whatever justifications I provide, some readers will inevitably find the contrast difficult to accept. Yet I stand in good company. Even Plutarch, the inimitable father of biographers, did not flinch from drawing uncomfortable parallels. He often placed the noble beside the ignoble – not to equate them, but to reveal the full spectrum of human character. One of his most striking juxtapositions appears in his “Life of Nicias and Crassus”: Nicias, the cautious and devout Athenian general, was renowned for his moral uprightness; Crassus, by contrast, was a Roman magnate consumed by greed, whose lust for wealth led to his catastrophic and humiliating end.

It is in this spirit – not of levelling, but of illumination- that I place these three voices side by side. Let us be clear: they are not equals. To do so is not to weigh them on the same scale of achievement or virtue. Indeed, for the one who symbolises decline, even being mentioned in the company of the other two may be his greatest triumph – like a forgotten footnote elevated by accident into the body of a great text. History offers parallels. Alcibiades walked beside Socrates but never shared his soul. Seneca advised Nero, but no virtue rubbed off. And Erostratus, who burned down the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, did so not out of hatred or ideology, but, as he confessed under torture, simply to be remembered. The Ephesians, appalled by his crime, forbade the mention of his name. Yet history, ever ironic, preserved it. As my old teacher, Fr. Collins Okeke, would say, he is remembered “for the instructiveness of his errors.”

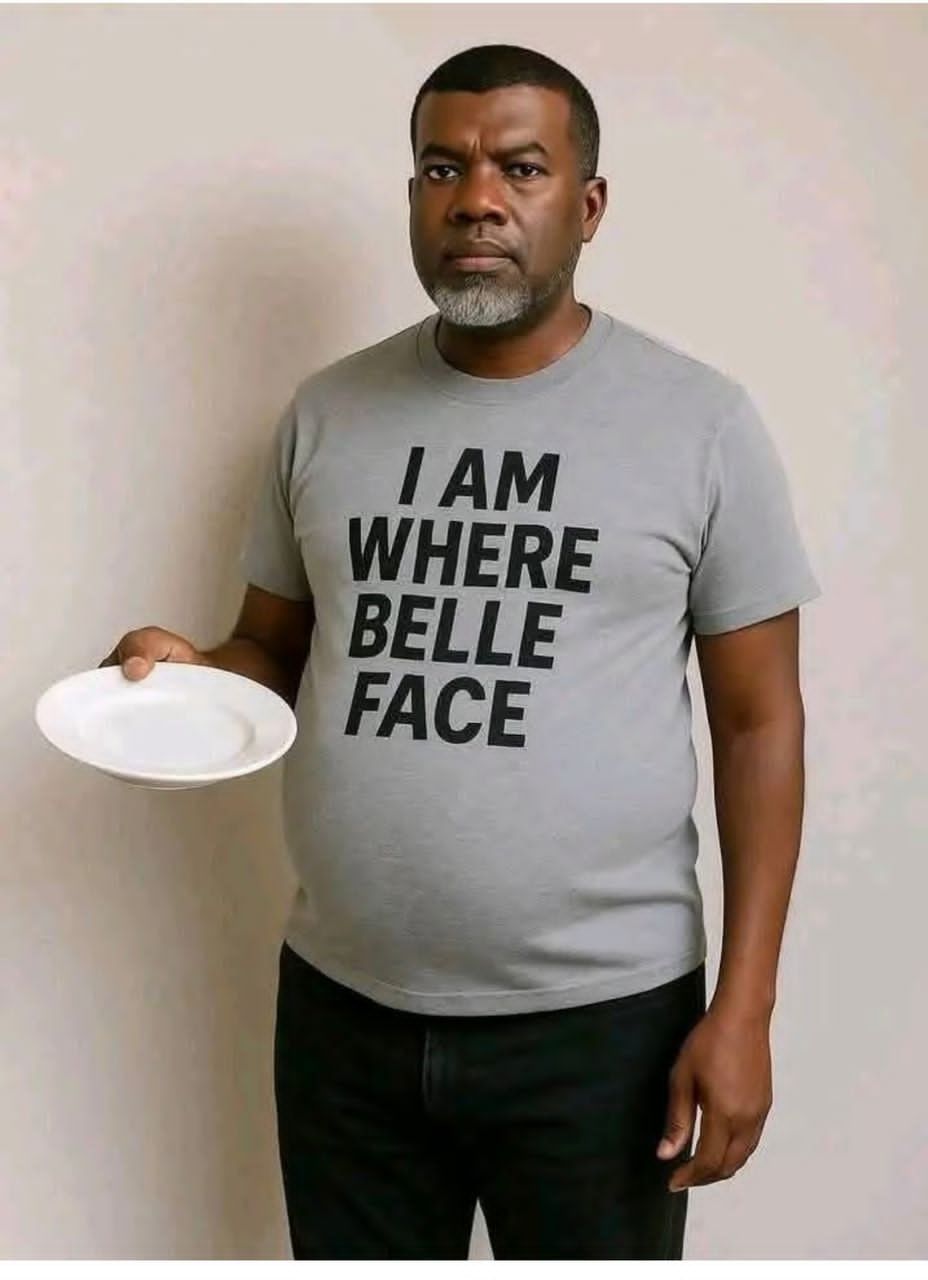

And so it is with Reno Omokri – a modern-day, digital Erostratus. He does not build; he burns. He does not seek the good, the true, or the beautiful, but the viral. He thrives on attention, even if it comes through distortion, provocation, or untruth. Like Erostratus, his greatest fear is not being wrong, but being forgotten and ultimately denied of handouts from government.

And so in Nigeria, we have our own tragic triangle: the voice that uplifts, the one that once thundered but now echoes hollow and must be draggged at his great age to Coastal road under construction, and the one that fills the air with sound but says nothing. The question then arises: where do you belong? Whose voice do you follow in this age of national confusion?

For many, the answer became clearer when Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie described Mr. Peter Obi as “the most inspiring Nigerian that we know” during the unveiling of her newest work, “Dreams Count.” Her words did not merely flutter on the air like praise from a celebrity. They landed like stone on water, sending deliberate ripples through the moral waters of the Nigerian public square. In a nation long famished of honest affirmation and burdened by glib endorsements, her remark came as an intellectual and ethical intervention.

It was, in that moment, as though the late Chinua Achebe spoke again through her: calm, unhurried, but cutting to the soul of a nation. For those who have eyes to see, Chimamanda is quietly assuming the role that Chinua Achebe once played – the literary conscience of a drifting people. Just as I once prophesied, that Bishop Peter Ebele Okpaleke would one day become a Cardinal, so too do I believe that Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is a Nobel Laureate in the making

Nigeria does not lack voices. It resounds daily with declarations, arguments, and verbal pyrotechnics. What we lack is moral gravity – voices that do not merely say things, but mean something. Voices that do not perform, but provoke thought. Chimamanda’s voice, polished by literary achievement and sharpened by philosophical clarity, has become one of those rare instruments in our national orchestra: tuned not to the rhythms of tribalism or personal gain, but to truth.

She has not waited for power to call her into relevance. She has claimed relevance by the quality of her ideas and the courage of her convictions. Where others twist, she stands straight. Where others hedge their words, she speaks plainly. And where many have grown silent out of convenience, she has chosen the risk of speaking.

But to fully appreciate Chimamanda’s rising role, we must confront the tragic descent of another once-towering figure: Professor Wole Soyinka.

For decades, Soyinka was not just a Nobel Laureate; he was a national conscience. His voice thundered against military despotism, injustice, and abuse. We quoted him with reverence. We looked to him in moments of darkness, and we found light. We remember the role he played during the Biafran War.

In recent years, when the nation cried out for clarity, Soyinka too often offered fog. When moral guidance was needed, he spoke in tongues. On matters where silence would have been wiser than equivocation, he equivocated. Many of us – especially the younger generation – watched in confusion as our literary lion appeared to lean toward the very structures of power he once resisted with fire and fury. He even crossed swords – in articles and books – with the great editor, Mr. Sunny Igboanugo. Sunny, who by generational and intellectual propriety ought to lay prostrate before Soyinka, was instead found lecturing him on the need to retire his pen gracefully, before his legacy is overtaken by contradictions.

Let it not be misunderstood: we do not expect infallibility from our elders. But we do expect consistency. We do expect that those who taught us to speak truth to power would not later spend their capital deflecting truth for the sake of association. And in the void left by this disappointment, Chimamanda stepped in – not as a replacement, but as a rescue.

Now enter Reno Omokri. The contrast is painful but necessary. Reno has built nothing remotely comparable to the intellectual or moral stature of either Soyinka or Chimamanda. Just as Sunny Igboanugo is Editor-in-Chief in the realm of letters, Reno is the Tweeter-in-Chief in the theatre of noise. His tweets often reveal not the depth of a thinker, but the contradictions of a charlatan – quick to pretend to moralize, quicker to contradict.

When Reno speaks, it is rarely to elevate; it is usually to provoke. His targets are predictable; his methods, mechanical. Like a man addicted to echo chambers, he plays to the crowd, feeding them not with insight but with spectacle. He mimics the language of justice, but it serves only to mask a deeper opportunism. While Chimamanda’s words build bridges between thought and action, Reno’s daily diatribes burn any bridge that might lead to honest national reflection.

This is not merely about Chimamanda, Soyinka, or Reno. This is about what kind of public culture we are cultivating in Nigeria. It is about the voices we elevate and the values we celebrate. It is about whether we will continue to treat intellect as a tool of convenience or restore it as a weapon of conscience.

When the chorus of reactionary voices from Anambra led by Croesus’ puppeteers attempted to assail Chimamanda – for her positions on land matter, I responded, then as now, that there is no serious basis for comparison. I recalled the ancient philosopher Democritus, who once said he would rather discover a single demonstration in geometry than acquire all the riches of the world or even ascend the throne of Persia. One cannot compare riches or power with the enduring dignity of truth and knowledge – for the former fades with time, but the latter remains, instructive and eternal.

Chimamanda belongs to the lineage of those who seek truth – not applause, not retweets, not government appointments. And it is this rare moral instinct that separates the enduring from the passing.

Yes, we, including Reno, belong to her generation. And if our generation is to mean anything in the annals of Nigerian history, we must become a generation of correctives, not a generation of cynics. We must not repeat the errors of those who let their moral clarity age into bitterness or who traded the struggle for freedom for seats at the table of comfort as Reno does. Ours must be a revolution understood as the wedding out of nonsense that have accumulated in our national lives.

I mean we must uproot the mediocrity that governs our national imagination. We must stop mistaking eloquence for enlightenment, and noise for knowledge. We must reject the idea that being “popular” online makes one right. We must recover our standards. And we must reward those who carry the heavy burden of truth with grace and grit – even when it costs them popularity.

If we do not, we will end up with more Renos – loud, reactive, shallow – and fewer Chimamandas – measured, courageous, and profound. And history is not kind to nations who forget how to distinguish between the two.

We are a broken nation. We are not in crisis simply because of bad roads, poor electricity, or weak naira. We are in crisis because our thinking has decayed. And from that decay springs every other dysfunction.

In such a nation, voices matter. But not all voices – only the right ones. The ones that stir us not into rage, but into responsibility. That do not pander to our divisions, but challenge our assumptions. That do not crave applause, but strive to be useful.

One voice offers clarity, another breeds confusion. One gives us hope, the other peddles distraction. One might just help us rebuild; the other reminds us – almost daily – why we fell. In a nation yearning for moral anchorage, those who truly love Nigeria and desire her progress find themselves drawn to Peter Obi, not just as a man, but as a symbol of what public life could be if guided by conscience. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, with the poise of the public intellectual and the precision of a moral seismograph, recognised this when she called him “the most inspiring Nigerian that we know.” In that simple declaration, she offered a counter-narrative to a culture increasingly polluted by noise.

And then there is Reno Omokri – a man who thrives not on clarity but on commotion; not on principle, but on performance. He does not inspire, he distracts. His presence in the national discourse is not a contribution, but a corrosion. Still, history, with its quiet discipline, knows how to distinguish between the voice that built and the one that merely echoed. Between those who stirred us to action, and those who screamed into the void.

Leave a Reply